Overview

Bloomingdale is composed of five sub-divisions: the original Bloomingdale plat of 1889, LeDroit Park, LeDroit Park Addition, Dobbins Addition, and the Moore & Barbour Addition. Portions of the Dobbins Addition once belonged to the Prospect Hill Cemetery, which moved from Seventh Street downtown to this rural location in 1858. In the late 1890s, Congress purchased land from the cemetery in order to extend North Capitol Street, creating a small swath of land west of North Capitol Street that was severed from the cemetery. In the 1920s, that parcel of land was developed with front-porch row houses.

Bloomingdale is composed of five sub-divisions: the original Bloomingdale plat of 1889, LeDroit Park, LeDroit Park Addition, Dobbins Addition, and the Moore & Barbour Addition. Portions of the Dobbins Addition once belonged to the Prospect Hill Cemetery, which moved from Seventh Street downtown to this rural location in 1858. In the late 1890s, Congress purchased land from the cemetery in order to extend North Capitol Street, creating a small swath of land west of North Capitol Street that was severed from the cemetery. In the 1920s, that parcel of land was developed with front-porch row houses.

The Bloomingdale neighborhood derives its name from the nineteenth-century estate of George and Emily Beale that was located near the intersection of North Capitol Street and Florida Avenue, NW. In 1889, after the death of the Beales, the land, which ran from Florida Avenue to T Street, was platted for residential development. The streets were laid out in conformance with the L’Enfant grid which was not the usual practice for subdivisions prior to the Federal Highway Act of 1893. Sold by Moore & Barbour Realtors, prices for the lots ranged from $75 for a mid-block site in the northern portion of the subdivision to $200 for a corner site in the southern portion. The Eckington & Soldiers Home Railroad, Washington’s first electric line which opened in 1888, originating at Mt. Vernon Square and 7th Street, NW, was extended north of Florida Avenue along North Capitol Street to the entrance of the Glenwood Cemetery and to Soldiers’ Home in 1894.

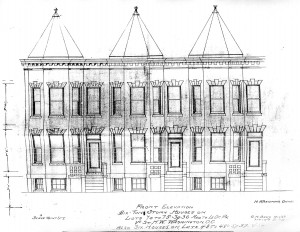

Bloomingdale became easily accessible to those employed downtown and, within a few short years, four more subdivisions were platted. Between 1903 and 1908, Wardman built 180 row houses in Bloomingdale. Twenty-seven were row-house flats; eighty were single-family row houses; seventy-three were front-porch row houses. During these years, Wardman bought and sold properties on a daily basis, and in some instances, profited as little as $200 per house. His total profit for five years of work in Bloomingdale was probably about $50,000, a tidy sum at that time. But that was only a portion of his business, for he was just as active in Columbia Heights and Mount Pleasant during this period. By 1906, at the age of only thirty-four, Wardman’s reputation was such that his name warranted mention on advertisements. The Baist maps show that in 1896, two years after the extension of the trolley line, development in Bloomingdale was minimal. By 1907, few vacant lots remained. A year later, Wardman built his last project in Bloomingdale.

Bloomingdale became easily accessible to those employed downtown and, within a few short years, four more subdivisions were platted. Between 1903 and 1908, Wardman built 180 row houses in Bloomingdale. Twenty-seven were row-house flats; eighty were single-family row houses; seventy-three were front-porch row houses. During these years, Wardman bought and sold properties on a daily basis, and in some instances, profited as little as $200 per house. His total profit for five years of work in Bloomingdale was probably about $50,000, a tidy sum at that time. But that was only a portion of his business, for he was just as active in Columbia Heights and Mount Pleasant during this period. By 1906, at the age of only thirty-four, Wardman’s reputation was such that his name warranted mention on advertisements. The Baist maps show that in 1896, two years after the extension of the trolley line, development in Bloomingdale was minimal. By 1907, few vacant lots remained. A year later, Wardman built his last project in Bloomingdale.